The Venice Biennale sparks surreal conversations between past and present in ‘Milk of Dreams’, curated by Cecilia Alemani and Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity, curated by Grazine Subelyte, Associate Curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

“The long tentacles of vision and understanding have withdrawn and all that is left to me is the ragged black hole of my loss. Loss and the world around. A noisy puzzle whose solution is another puzzle noisier and more stupid. The circle widens toward nothing. The answer is hiding somewhere if I could only read.” ― Leonora Carrington, The Seventh Horse And Other Tales

Why do we pretend that the world is not a ridiculous, theatrical fiasco? The Venetians acknowledge this continuously with Carnival and La Biennale when the whole corpus arts descend on the glittering, tragically precarious city perched on a forest of petrified trees in a waterlogged lagoon. Fitting then that the 59th Biennale takes its curatorial title from a children’s book of fairytales by the Surrealist Anglo-Irish/ Mexican artist Leonora Carrington’s Milk of Dreams. To Cecilia Alemani, nominated as curator in January 2020, Carrington’s surreal, irreverent, and sardonic body of work articulates “our growing consciousness of the nonhuman world and the forces that inhabit it.” Her creations — hundreds of paintings, sculptures, and objects, two novels, a memoir, and a fantastically morbid collection of stories — have rarely been exhibited since her death in 2011. Yet, each time her work is seen, it seems more prescient.

Why? Surrealist art, with its outlandish, hyper juxtapositions, appealed to Carrington for the same reasons it seems relevant now – it highlights human folly but also celebrates the wildness of dreams, reminding us – perhaps – that whilst we live in a war-torn, pandemic ravaged, carbon choked world, we might imagine an alternative. So, like many of us, Alemani began curating remotely, interviewing thousands of artists on zoom, “Unable to experience their work physically, I was surprised by the intimate and confessional nature of our conversations as if it was the end of the world… These conversations led to numerous existential questions – in particular, how is the definition of a human changing and what would the world look like without humans?”

To Alemani, our time mirrors the birth of Surrealism – a reality shattered by mechanical war, Spanish flu and toxic nationalism. It gave form to the unimaginable through what Henri Bergson calls “something mechanical encrusted upon the living”. As our technologically led, carbon addicted lives are mediated thus, it seems prophetic. And yet, for all their avant-garde sensibility, the torchbearers of Surrealism did not precisely see women as equal partners. In his essay “The New Colors of Spectral Sex Appeal” (1934), Salvador Dali prophesied that the sexual attractiveness of the modern woman would derive from “the disarticulation and distortion of her anatomy”. Precisely because the Surrealists viewed women as artificial beings—their bodies manipulable, their spirits elusive – their work seemed almost irrelevant until curators began to revise the story and include the vision of women who had been there.

Alemani’s solution to this dilemma was to curate a virtually all-female show, replete with five historic time capsules. “By featuring women artists and cultural practitioners whose work was left on the fringes of male centre histories, serve as a starting point for critical reflection, tracing alternative genealogies and affinities past and present.” This new, alternative history includes 213 artists from 58 countries “who challenge the Western universal ideal of white male reason as a measure of all things and propose different alliances and porous, fantastic beings.” This is her rationale for curating predominantly female and gender nonconformist artists that “reflects an international scenario of great ferment.” However, something fundamental is missing – men. Instead of reclaiming the narrative, she reframes it entirely, but has she also sealed it off? Comedic and tragic at the same time, this one-sided story is why women were excluded from the conversation.

Whilst it highlights Alemani’s post-human thesis, she is also negating something that might aggressively manifest somewhere else. Those excluded tend to build their worlds (note collateral blockbuster shows of Kehinde Wiley, Anselm Keifer, Anish Kapoor, Raqib Shaw), which is tragically reflective of geopolitics… Alemani could never imagine that just before her show opened, a single white male would wage war on a sovereign state on European soil. Either we are asking the wrong questions, or we have not properly understood the past. Is this Alemani proposing a new, fantastical lineage or suggesting that this is where all human line ends?

Asserting her unconventional narrative was an essential part of Carrington’s story, and it underscores Alemani’s Biennale. Art was the vehicle for her reincarnation as a multiple and quixotic being (“an androgyne, the Moon, the Holy Ghost, a gipsy, an acrobat, Leonora Carrington, and a woman”). Her first Self-Portrait depicts wild, untamed hair and a white horse galloping away to freedom. Carrington also invented her creation myth, stating she had not been born but made. Merve Emre says, in her essay How Leonora Carrington Feminised Surrealism for the New Yorker, “One melancholy day, her mother, bloated by chocolate truffles, oyster purée, and cold pheasant… had lain on top of a machine… a marvellous contraption, designed to extract hundreds of gallons of semen from animals—pigs, cockerels, stallions, urchins, bats, ducks—and… bring its user to the most spectacular orgasm… Leonora was conceived from this communion of human, animal, and machine.”

A rebellious visionary, Carrington rejected both convention and nationalism. Escaping to France with Max Ernst, then Mexico when WWII ripped Europe apart, she made her home in the country Andre Breton dubbed “the most surreal nation on earth”. Having been introduced to Celtic mythology by her Irish mother, she fast absorbed astrological and Mayan imagery whilst expanding her knowledge of the occult, Kabbalah and Buddhism. As a result, her paintings are full of masked, gnomic beings, hyena-faced, bird-bodied creatures that hover magically between the familiar and strange. Following the birth of her two children, she drew whimsical, hybrid creatures on her walls, later collected in the booklet Milk of Dreams. Erme says, “Surrealist art… invited her to cavort with nonhuman creatures, drawing on their beauty and suffering to make tame ideas about character and plot more porous, elastic, and gloriously unhinged.”

Alemani’s opening curatorial statement in the Central Pavilion suggests we are “part of the symbiotic web of interdependencies that bind us to each other. By enlisting localised or indigenous forms of thought and hoping they will be textually and figuratively absorbed by the institutions that uphold and define the history of art….” It is worth noting here that Alemani is married to the 55th Biennale curator Massimiliano Gioni (a New York power art couple), with whom she also had a child. Weaving three themes through the Central Pavilion and Arsenale – body and metamorphosis, individual and technology, bodies and earth – Alemani anchors her show with 5 “time capsules,” which resurrects landmark historic shows. As a whole, the experience is like falling into a cauldron, one that reflects the dissolution of systems and the world as we know it.

The show opens with Katharina Fritsch’s giant Elephant (1987), infinitely reflected in mirrored walls. Is Alemani milking the elephant metaphor to highlight the problematic duality of being a woman artist – creator and creative? Is this a nod to Carrington’s Self Portrait, in which the concept of duality is explored using a mirror to assert the duality of the self – of being an observer and observed? Is she referring to Lacan’s mirror stage? Like infants who delight in recognising themselves, are we stuck in a permanent state of subjectivity or “imaginary order”? In Some reflections on the Ego (1953), he says, “…it marks a decisive turning-point in the mental development of the child… (and) it typifies an essential libidinal relationship with the body image.”

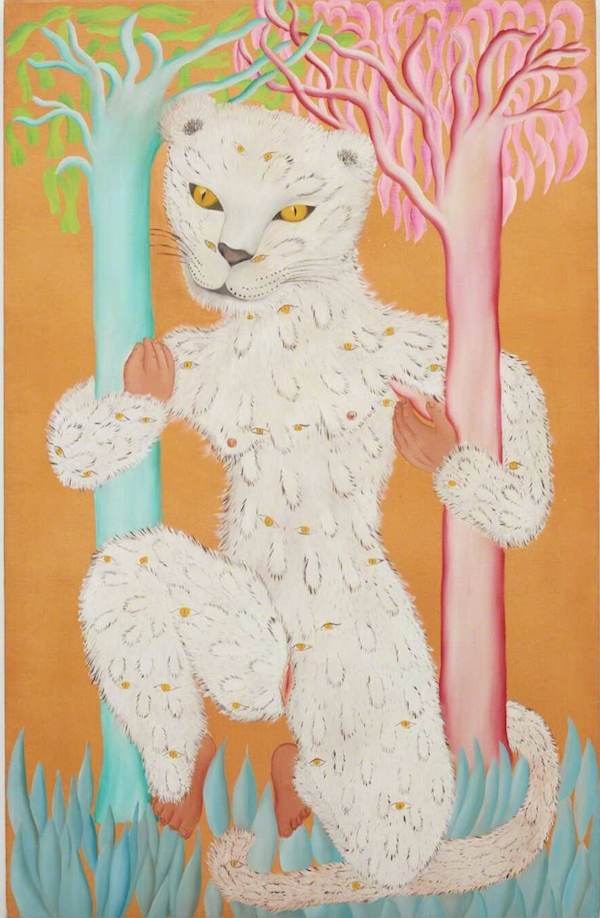

In an adjoining room, Cecelia Vicunya’s Leopard de Ojitos (1976) seems to offer an answer. Seen through the delicate spiderweb of her site-specific work, it is accompanied by the words:

“She illuminates what is.

The eye is zero

Sex and emptiness

Are the hole of the wheel

That spins

The world

The eyes of instinct open when we allow ourselves to be carried away by a form of knowledge that is richer and deeper than rationality. It could be that the eyes are hidden in the hair, waiting to see.” Cecilia Vicuna

There is so much to see here, past and present, I feel blinded. “Time capsules” staged by Milan based @fabricaforma of works that were “previously overlooked” act as “proof” that artists have been pushing alternative agendas for decades. But precisely because they comprise an all-female cast, I struggle. I want to enrich the visual history I am familiar with and find myself somewhere un-relatable. In the Giardini, we encounter an artist’s attempt to dialogue with or imaginatively leap over national pavilions’ worn definitions and dusty categories. In Alemani’s global exhibition, we find a host of well-deserving female, non-binary and non-white artists, freewheeling out of context. Yet, excluding the men relegates many of these artists to a separate history. Still, we are deprived of a crucial frisson: that powerful, sexual energy that ultimately births something new.

This feeling is compounded in the Arsenale as a monumental sightless sphinx greets us: Simone Leigh’s Brick House; the eyeless bronze head of a black woman emerges from a domed cylinder reminiscent of an earthen dwelling from Chad or Cameroon. Unfortunately, part artefact, part shelter, recalls Hirst’s fake bronze from his critically disastrous show, Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. Except this bronze is authentic, and the sombre, monochrome works around it are from the late Cuban Belkis Ayon, who tragically never made it to Venice. (Top Photo)

Surreal indeed, but also maddening. I am doubting everything. It makes me think of Carrington’s psychotic break and a narrow escape from the asylum. Separated from Ernst in WWII and paralysed by anxiety and delusions, she was given electroconvulsive therapy, powerful convulsants and barbiturates in Spain, whereby her estranged parents decided to send her to a sanatorium in South Africa. Fortunately, en route, she contacted Renato Leduc, poet and Mexican Ambassador, with whom she escaped to New York, then on to Mexico, where she lived for the rest of her life. So, where do we go from here?

Alemani seems to anticipate this and augment our sense of the surreal in the next room with five giant vessels by Gabriel Chaile of Spanish, African-Arab and Indigenous Candelarian heritage (Argentina). After the ponderous heft of Simone Leigh’s Golden Lion-winning bronze, Chile’s clay bird pots bewilder and stupefy the viewer in a kind of Alice in Wonderland moment. His long-standing exploration of impoverished communities, rituals, and artistic customs has resulted in poetically surreal creations, sacred and profane; they blow up the trans-historicisation of form. Two key concepts underscore his practice: the engineering of need, creating objects that attempt to improve the conditions of a specific borderline situation; and the genealogy of shape, which acknowledges that every object in its historical repetition provides a story to tell, one that is recovered and updated concerning the new context. Rebirth.

Later on, we see this idea mirrored in five vessels by Magdalene Odundo (Kenya, 1950) from her Symmetrical Series (2017). Following the long tradition of associating women’s bodies with architecture or vessels, after shaping the clay, she uses ultra-refined terra sigillata slip, burnishes her surfaces with stones and polishing tools, and fires her objects multiple times, transforming the clay into rich red-orange and black sculptures. She sees them as having an inside and an outside “I think very much of the body itself as a vessel; it contains us as people.” This idea is expanded in two stand out installations: Sandra Vasquez de la Horra’s drawings of women, sealed with beeswax inside a wooden house-like structure, and Emma Talbot’s ecstatic painted silk sheath, Where Do We Come From, What Are We, Where are We Going? (2021) that articulates her wish to escape from our environmentally catastrophic present.

Carrington once stated, “We, women, are animals conditioned by maternity… For female animals, love-making, which is followed by the great drama of the birth of a new animal, pushes us into the depths of the biological cave.” In the absence of men, the tension was missing, but so was the sex. It was a night without day; I could hear Carrington say, “I saw the reflection of the moon in the water but was horrified to see there was no moon in the sky: the moon had been drowned in the water.” This is fully manifest in the last, suffocating room, filled with rotting plants, symbolic of the desperate infertility of a lightless, single-sex world.

I was grateful for a pause in the Irish Pavilion, which occupies the final room in a row of curated spaces. The looped image of a simple grey Vent by Niamh O’Malley on a square LED screen. Taken from outside her Temple Bar Gallery Studios, where it disperses material dust from artistic production into the general atmosphere, it could be a metaphor for the process of art-making. In the catalogue for the show, Gather, O’Malley says, “In making something we might have cleared a place for encounter – and the gap produced, the distance itself, might be the thing. This is the texture of distance, the price of sight. Quiet now.”

As I stepped out into the pouring rain, which had turned the avenues into milky sludge encrusting our shoes, I wondered what we would all do with this milk thought. How would it nourish or deprive us of dreams for the future?

I found my answer elsewhere. Leonora Carrington also has a room dedicated to her in another landmark show, Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity, curated by Grazine Subelyte, Associate Curator, at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice; a thoughtful, balanced view of how this particular part of the past speaks to the present. Four years in the making, one might say the zeitgeist is at work or “as the surrealists would say, this was something predestined.” Unlike Alemani, guided by a book of fairytales, Guggenheim’s curator looked to Andre Breton’s L’Art Magique (1957) which traces the history of magic and sees it culminating in Surrealism. It is also a show that celebrates the beginning of women’s emancipation, and “women, who were largely invisible, are the beating heart of this show.”

For this, the show at Guggenheim triumphs. Whilst it was not lost on me that its star player, Max Ernst, had slept with, and married, three of the women headlining the show – first Carrington, then Guggenheim, and finally Dorothea Tanning, one cannot argue that he did not see or value them. Art historians were slow to recognise the centrifugal force of these women, he did not. Nevertheless, I was honestly relieved to see Ernst’s work in this show; I reevaluated it and understood his role in the structural DNA of Surrealism. “Freud’s book Totem and Taboo (1913) defines magic as the omnipotence of thought, emphasising that thoughts can affect the material world/reality – and one might say art,” says Sublette.

The first time Carrington saw a Surrealist painting in Paris, she was ten years old. Something in that work gave her permission to rebel: she was expelled from two consecutive schools, attended Mrs Penrose’s Academy of Art in Florence, and went back to England to be presented at Court but bought a copy of Aldous Huxley’s Eyeless in Gaza (1936) to read instead. Then, seeing Ernst’s work at the International Surrealist Exhibition in London, In 1937, Carrington met him at a party and they eloped to Paris, where Ernst promptly separated from his wife. In 1938 they left Paris and settled in Saint Martin d’Ardèche in southern France. But then WWII intervened. Separated from Ernst (26 years her senior), Carrington suffered a nervous breakdown and then fled to Mexico.

Instead of censoring Ernst, Subelyte includes him, “Max Ernst was one of the greatest artists of the 20th century in my humble opinion.” A wonderfully radical statement in such an all-female moment, for which I was genuinely grateful. We cannot silence the men if we are to revise history legitimately; instead, this show outlines the magical exchange of love and creativity between them.

Arrested by the French authorities as a “hostile alien”, then discharged with the intercession of Paul Éluard, Ernst was arrested again by the Gestapo, his art was branded “degenerate”. Enter Peggy Guggenheim, with whom he escaped to the United States, leaving Carrington behind, and married in 1941. The following year, he met Dorothea Tanning at a party. He then went to her studio to consider her work for inclusion in the 1943 Exhibition by 31 Women at Guggenheim’s gallery Art of This Century. As Tanning recounts in her memoirs, he was enchanted by her iconic self-portrait Birthday (1942, Philadelphia Museum of Art). The two played chess, fell in love and spent the rest of their lives together. In 1954, Ernst was awarded the Grand Prize for painting at the Venice Biennale. Seventy-seven years later, Carrington joins him, and the circle is complete.

Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity is a testament to our human capacity to look beyond the human tragedy of reality into the realm of the unconscious – magic, dreams and even the occult – as a source of empowerment. There is a hidden dimension, invisible to the human eye. Subelyte shows us how Carrington harnessed the Surrealist cult of desire as an infinite source of creative inspiration. When painting, she used small brushstroke techniques to build up layers in a meticulous, alchemical process, bringing magically real scenes that seem to prefigure her destiny. Her portrait of Max Ernst is spellbinding for its lavish, feathery details, just as his masterpiece, Attirement of the Bride (1940), enchants us with a bare white body framed in brilliant plumage a homage to the romance novel Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz (1616). As Merve Emre says, “Shouldn’t the two be allies in a planetary war against débutante balls, against kings and queens and empires, against the cannibalising machinery of capital, which takes the domination of women and nature as its origin point?” Yes!

Make love, not war… I will forever be haunted by Dali’s masterpiece in the last room of the exhibition, Uranium and Atomica Melancholia Idyll (1945), which describes the horror of WWII but seems to prefigure the present war in Ukraine, not in the least for the small, fragile bubbles of yellow and blue. I think of the haunting wall of portraits of Ukrainian mothers who have lost their sons in the war at the Pinchuk Art Centre in Misericordia – a world without boys, without men, is a dead world. I am reminded that Carrington was also a founding member of the women’s liberation movement in Mexico during the 1970s. Unlike Alemani, Subelyte’s show is focused on psychic freedom and the belief that such freedom cannot be achieved until political freedom is also accomplished.

As I leave, I select Sam Fender’s “Seventeen Going Under” on my playlist and walk out into the glorious, soaking rain.

Top Photo: Simone Leigh Brick House, 2019 Words/Photos Nico Kos Earle © 2022 Artlyst