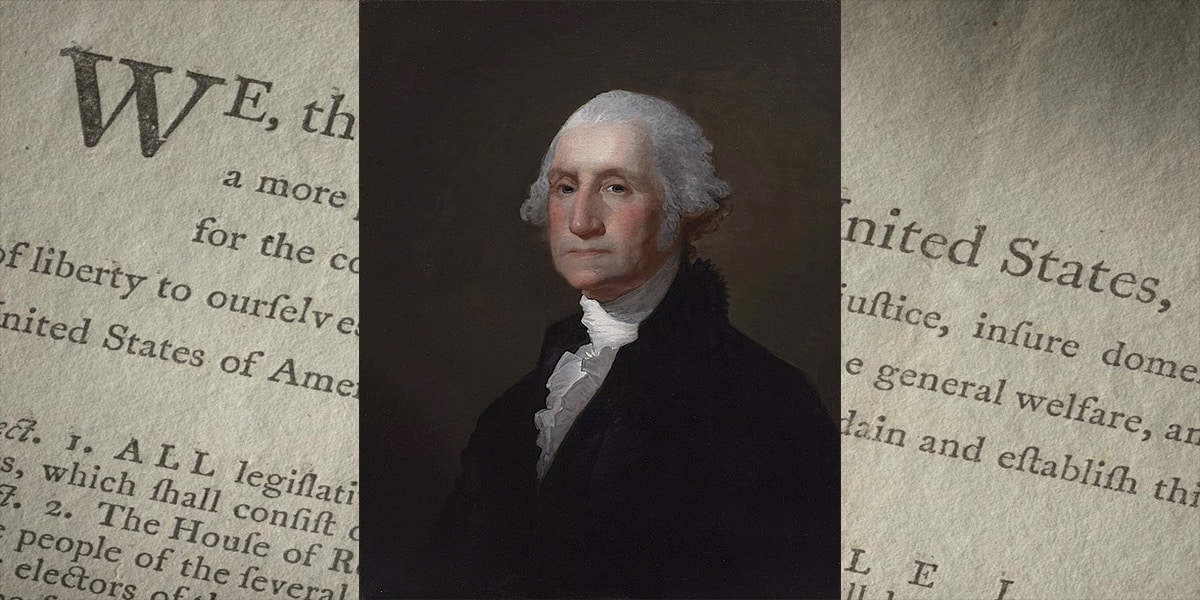

Christie’s marks America’s 250th birthday in January 2026 by rolling out its largest-ever Americana Week: nine sales, roughly 700 lots, including a signed copy of the Emancipation Proclamation and the original contract that created Apple Computers. Adding this wow factor, a portrait of George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart, the artist who created the image used on the US dollar bill, is up for grabs.

The iconic painting goes under the hammer on 23 January, with an estimate of $500,000 to $1 million. This lot, however, is expected to surpass the estimate by several million dollars. This particular painting comes with a story that took Christie’s specialists years to unravel.

Stuart painted Washington more than any other artist, not because Washington enjoyed it—he famously didn’t—but because Stuart understood something early on: this face would travel. “Washington was famously not fond of sitting for artists,” Martha Willoughby, a consultant specialist in Christie’s Americana department, told me. Yes, there was humility involved. There was also the small matter of boredom. Sitting still, endlessly, while someone scrutinised your jawline was not how Washington liked to spend his afternoons.

Stuart, however, was persistent. In 1794, newly released from a debtor’s prison in Dublin after burning through money and goodwill in London, he secured a letter of introduction from Chief Justice John Jay. He knew exactly what he was doing. Washington’s likeness, reproduced and circulated, could be a financial lifeline—or more than that.

What followed was a sequence of images that would quietly become some of the most recognisable portraits in American history—the Vaughan type in 1795. The Athenaeum type was set in early 1796. And then, a few months later, the full-length Lansdowne portrait. Each served a different purpose. Each refined the last.

The Athenaeum type, commissioned by Martha Washington, became the most ubiquitous. By the time Stuart finished Washington’s head, he knew he’d nailed it. This was the version. So he did something that would infuriate his patron and secure his income: he left the painting unfinished, kept it, and began producing copies. Stuart jokingly referred to them as his “$100 bills.” It wasn’t really a joke.

The version heading to Christie’s next January is an Athenaeum-type portrait, but with a twist. Clarkson University, which consigned the work, claimed it had been commissioned not by the Washingtons but by James Madison. That raised eyebrows. “I was very suspicious,” Willoughby said, plainly.

Stuart scholarship relies heavily on reference volumes compiled in the 1920s and 1930s. This painting appears in those books, but without any mention of Madison: no commission, no correspondence, no paper trail. With Stuart, that’s not unusual—but it’s never comfortable.

So Christie’s went digging. The first breakthrough came in the form of a catalogue compiled in the 1850s by William Henry Aspinwall, the American magnate who owned the painting at the time. It clearly described the work as originating in Madison. Then came the clincher: a note from Madison’s secretary. In it, he explains that he personally persuaded Stuart to finally complete the portrait in 1811, after it had been commissioned and paid for seven years earlier. Other accounts place the painting in Madison’s home as early as 1806. With Stuart, timelines slide. Payments stall. Paintings linger.

Madison, it turns out, commissioned two portraits: one of Washington and one of himself. The Washington was displayed more prominently. After Madison’s death, it passed to his wife, then to his son, then onward through a chain of American collectors: Aspinwall, industrialist James W. Ellsworth, St. Louis collector William K. Bixby, and eventually Richard L. Clarkson, whose family founded Clarkson University.

At the university, the painting developed a second life. In one episode that now feels faintly surreal, three fraternity students stole it as part of a prank. They were caught. They went to jail. The second-degree grand larceny charges were later expunged. The painting, unbothered, returned to the wall.

Today, roughly 75 Athenaeum-type Washington portraits are thought to exist. “It’s very hard to get an exact number, because people disagree,” Willoughby said. Stuart didn’t sign his work. He believed his skill was signature enough. As a result, the accepted pool of works shifts with each discovery or debunking.

What is clear is that demand has been building. Christie’s has sold seven Athenaeum-type Washingtons in the last decade. Eight have appeared on the market in that time. Success breeds confidence. Confidence brings more examples out of hiding. This one, though, has momentum. The existing auction record for an Athenaeum-type portrait sits at $1.06 million, set in 2015. Christie’s believes this could pose a challenge.

Placed within the context of Americana Week, the painting does more than commemorate an anniversary. It reminds us how American history has been packaged, copied, circulated, and sold from the very beginning. Stuart understood that better than most. He didn’t just paint Washington. He reproduced him. And two and a half centuries on, the market is still catching up.