The reimagining and recycling of Hollywood movie iconography in contemporary art, and the way that movies live on in our personal and cultural memories, are explored in the exhibition Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact, opening on November 7, 2015 at the Museum of the Moving Image NY. Organized by independent curator and scholar Robert M. Rubin, the exhibition includes 120 works of 40 artists and directors that dissect, appropriate, and redefine some of the past century’s most iconic films through photography, drawing, sculpture, print, and video. They are joined by a selection of rare film ephemera re-positioned as artworks ranging from costume designs for Rosemary’s Baby to the complete original key book stills from The 39 Steps. With a nod to the “walkers,” or zombies, from the TV series The Walking Dead, the exhibition’s title references the lingering power of film detritus on the imagination of the living.

“As an institution dedicated to the advancement of our cultural and intellectual understanding of the moving image, we are very enthusiastic about taking this significant step forward for our institution,” explained Museum of the Moving Image Executive Director Carl Goodman. “This is easily the largest, most ambitious contemporary art exhibition mounted by the Museum, and the first to include works-painting, photography, and sculpture-that are not media-based. These works form the foundation of Walkers because of their deep thematic connection to popular cinema.”

Of the many forms of media that arose in the twentieth century, there is perhaps none more enduring than Hollywood cinema. In the twenty-first century, films are distributed digitally in movie theaters and beyond, and increasingly on screens smaller than a postcard; images and clips from films become carriers of memes and diverge from the source material. With the Walkers exhibition, curator Robert M. Rubin asks, “If the twentieth century was the century of the moving image, and the twenty-first century is the century of the digital image, what happens to all those celluloid signs in a virtual world?”

The titular “Walkers” pays a lighthearted homage to the reanimated zombies depicted in the notable television series The Walking Dead, referencing the rich afterlives of iconic Hollywood imagery in circulation today. In this vein, the exhibition engages the role classic Hollywood film has occupied in the public imagination; one so pervasive that it often measures understandings of reality: “Isn’t it just like in the movies?” The films themselves have often become separate from their component conventions and visuals.

Twentieth-century cinema produced, and was produced through, a wealth of print media. Known by collectors as “cinema paper,” the promotional posters, headshots, set photographs, and printed drafts of scripts have also become increasingly outmoded in the era of YouTube, social media marketing, and digital storage and distribution. Through artistic intervention, be it direct editing of the films themselves, sampling of individual stills, re-contextualizing and remixing of imagery, a home video reading of a film script, or a revisiting of an advertisement, Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact examines the role of the celluloid image in a digital culture.

Artists on view: Nada Ackel, Francis Alÿs, Richard Avedon, Fiona Banner, Saul Bass, Cindy Bernard, Pierre Bismuth, John Bock, Jim Campbell, Gregory Chatonsky, Gregory Crewdson, Brice Dellsperger, Jeff Desom, John Divola, Mark Flood, Aurélien Froment, Michel Gondry, Douglas Gordon, Robert Heinecken, Gregor Hildebrandt, Alex Israel, Larry Johnson, Isaac Julien, Martin Kippenberger, Agnieszka Kurant, Jean-Jacques Lebel,

Guy Maddin, Mary Ellen Mark, Adam McEwen, Ivan Messac, Kristen Morgin, Bill Morrison, Richard Mosse, Simon Norfolk, Richard Prince, Nicolas Provost, Bernard Rancillac, Tom Sachs, Manuel Saiz, Adam Savage, Hans Schabus, Leanne Shapton, John Stezaker, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Piotr Uklanski, Ming Wong, Mario Ybarra Jr.

The exhibition is divided into eleven separate “takes,” or sections that riff on different themes that emerge from the material. In one example, the section “Heart of Darkness” spotlights the story of Joseph Conrad’s novel in film as it plays out over forty years: Orson Welles’s failed adaptation-which led to his creation of Citizen Kaneas a compromise-is resurrected through Fiona Banner’s 2012 promotional campaign for the film in The Greatest Film Never Made. They are joined by costume and costume drawings, a “Death From Above” playing card, and Mary Ellen Mark’s set photography of Marlon Brando both in and out of character from Apocalypse Now. “Dial M for Meta” illustrates the many appearances of the works of Alfred Hitchcock, who Rubin describes as the “most referenced director in contemporary art”: Manuel Saiz presents a copy of North by Northwestrented from a video store, edited by the artist, and returned. Jim Campbell’s lightboxes edit Psycho into a single averaged still image, while Gregory Chatonsky’s Vertigo at Home reconstructs the film via Google Street View. As a final sampling, “The Big House” examines our understanding of crime and punishment through the scope of Hollywood. Tom Sachs’s whimsical Godfather Viewing Station joins Mario Ybarra Jr.’s Scarface Museum, displaying the artist’s collection of memorabilia from the film, while the over-the-top melodrama of an original poster for the 1958 film I Want to Live depicting Susan Hayward in an electric chair plays off the uncanny “reality” of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s portrait of a wax figure in an electric chair.

The Walkers exhibition will be accompanied by a screening series, presented in the Museum’s Sumner M. Redstone Theater. Select films will be introduced by artists in the show.

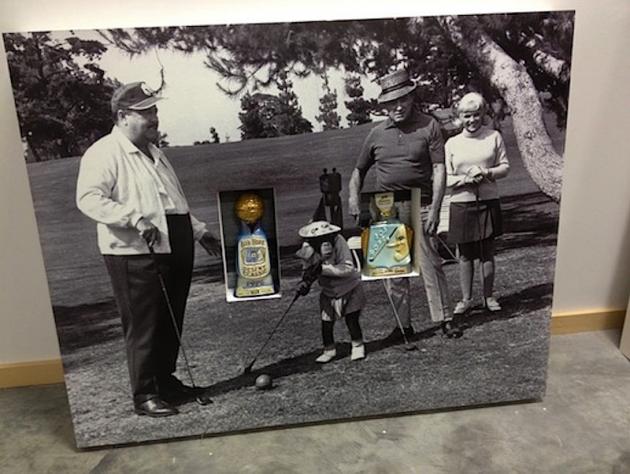

Top Photo: Richard Prince, Untitled (Bob Hope), 2012. © Richard Prince

Walkers: Hollywood Afterlives in Art and Artifact, opening on November 7, 2015 at the Museum of the Moving Image NY.