Sotheby’s spent the week polishing its trophies — a Klimt with a stratospheric estimate, a Frida Kahlo that ignited the room — but behind the polished glass and discreet lighting, a significant legal dispute involving a Modigliani has emerged.

It concerns a painting that was once sold with confidence. The plaintiff, a collector named Charles C. Cahn, Jr., has taken the auction house to the Supreme Court of the State of New York, alleging something along these lines: Sotheby’s refuses to resell a painting it sold him back in 2003 — a claimed Modigliani portrait of the artist’s dealer, despite a written agreement that should have guaranteed exactly that.

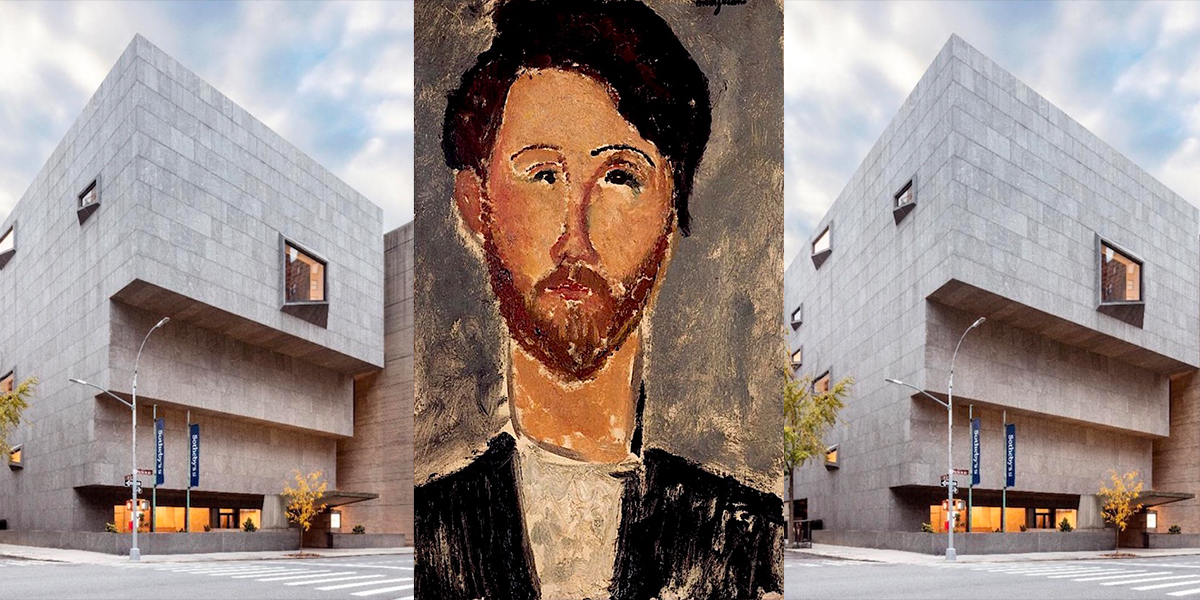

The painting, Portrait de Leopold Zborowski, dated 1917, wasn’t a stray footnote in Modigliani’s practice. According to Sotheby’s own catalogue at the time, it had been exhibited in the 1934 Modigliani retrospective at Kunsthalle Basel. It carried a clear provenance trail that even suggested Zborowski himself had once owned the artwork: a nice circularity, the dealer returning home.

Cahn now says Sotheby’s quietly changed its tune in late 2016 following an agreement signed by the plaintif with Sotheby’s. According to the lawsuit, the auction house told him — verbally, it seems — that the painting failed specific authenticity criteria and essentially had “no sale value in the international art market.” In other words, not Modigliani enough to sell. Sotheby’s hasn’t confirmed that it ever said any such thing, though Cahn’s lawyers have produced an agreement from that year in which Sotheby’s essentially offers a safety hatch: Cahn could consign the painting within fifteen years, and the house would cough up the original $1.55 million plus 2.5% compounded interest—a rather specific arrangement for a painting whose authenticity wasn’t supposed to be in doubt.

The issue now is that when Cahn finally tried to trigger that clause — approaching the house in June of this year — Sotheby’s allegedly responded with… nothing. No phone call, no email, no polite “we’re looking into it.” Nothing in September either, when his lawyer followed up. Silence, according to the lawsuit, has become Sotheby’s position. And silence, in the art market, is rarely neutral. It signals potential legal trouble and raises questions about transparency and accountability.

Cahn now wants $2.67 million — a number that covers the original price, the interest, perhaps a dash of exasperation. Sotheby’s, in classic No Comment mode, says it won’t remark on active litigation. Understandable. Though one imagines their communications team gritting its collective teeth, given the timing. It’s hard to parade nine-figure Klimts while simultaneously being accused of selling, and then refusing to touch, a dubious Modigliani.

And this is where the whole situation sits inside a much older, messier story: Modigliani forgeries have poisoned this market for decades. There are enough fake Modis in circulation to populate an entire shadow exhibition. Police raids, seized canvases, embarrassed experts — it’s practically its own art-historical genre. Anyone buying a “less expensive” Modigliani, even twenty years ago, should have expected some level of unease. That said, $1.55 million wasn’t pocket change in 2003. But compared to the $26.9 million achieved that same year by a blazing, indisputable Nu couché — or the $157.2 million Sotheby’s achieved for it again in 2018 — the Zborowski portrait was always sitting in the lower, affordable stratum of Modigliani’s work.

Authenticity remains central to this dispute. If Sotheby’s believed in 2003 that the painting was genuine, then a change of stance suggests a profound shift. This raises questions about the reliability of provenance and the integrity of the market, making the case more compelling for readers interested in art law and market ethics.

The lawsuit will carry on, and Sotheby’s will continue selling masterpieces at vertiginous prices. And somewhere in storage, the disputed Zborowski waits — a painting that may or may not be a Modigliani, depending on which year you go by.

After a week in which Sotheby’s has broken individual records and sold $706m across three sales, it should do the right thing and restore public confidence by biting the bullet and coughing up the amount agreed by the original contract, after all, litigation is expensive in the States. – PCR

Disclaimer: A little digging on the web has turned up this information. I am nearly sure that this is the Modigliani painting in question, but I could be proven wrong. Only Sotheby’s can confirm this.

Amedeo Modigliani

Description

Amedeo Modigliani

PORTRAIT DE LEOPOLD ZBOROWSKI

Signed Modigliani (upper right)

Oil on canvas

17 3/4 by 10 3/4 in. (46 by 29 cm)

Provenance

Léopold Zborowski, Paris (acquired from the artist)

E. Khoury, Paris (by 1933)

C.M. Michaelis, Esq., London (sold: Sotheby’s, London, May 4, 1960, lot 100)

T. Grange (acquired at the above sale)

Philippe Blou

Perls Gallery, New York (acquired from the above in 1991)

Acquired from the above in 1992

Exhibited

Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Exposition rétrospective Modigliani, 1933, no. 26

Basel, Kunsthalle, Rétrospective Modigliani, 1934, no. 18

Literature

Arthur Pfannsteil, Modigliani et son œuvre, Paris, 1956, no. 233, catalogued p. 129

J. Lanthemann, Modigliani, 1884-1920, Catalogue Raisonné, Barcelona, 1970, no. 227, illustrated p. 220

Catalogue Note

Léopold Zborowski (circa 1889-1932) was Modigliani’s primary dealer and confidant during the final years of the artist’s life. A Polish émigré from an upper-middle-class family near Lvov, Zborowski moved to Paris in 1910 to study literature, but could not make a living as an amateur poet. To support himself, he began trading rare books, manuscripts, sketches, and miniatures, and eventually tried his hand at dealing in fine art. Through his involvement in the bohemian circles of Paris he was introduced to the artists Moise Kisling and Maurice Utrillo, and offered to sell their works out of his apartment on the rue Joseph Bara. When he first saw Modigliani’s paintings at an exhibition in 1915, Zborowski had already formed a reputation as a fledgling dealer and decided to invest his energy in promoting the artist’s work. The young Italian painter had been represented by the well-established dealer Paul Guillaume up until that point. Still, he was flattered and intrigued by Zborowski’s attention and signed a contract with him in 1916. In the years that followed, Modigliani and Zborowski formed an intense personal and professional relationship, both depending on each other’s success and talent.

As his career developed under Zborowski’s support and encouragement, Modigliani refined his talent as a portrait painter, executing the likenesses of his friends, mistresses and fellow artists. Among the most well-regarded of these works are his portraits of Zbrowoski, including this one, which provides a straightforward depiction of the dealer looking directly at the viewer. In contrast to another well-known, more formal representation of him dressed in a suit and tie (see fig. 3), the figure in the present work is dressed more casually. The attention here is on his face rather than his accoutrements, similar to another portrait the artist completed in 1918 (see fig. 4). This frank representation reveals Zborowski’s approachability and Modigliani’s ease and familiarity with him, perhaps best demonstrated by the intimate way he paints his friend’s absorbing, green eyes.

This painting dates from 1917, and by then Modigliani had become widely known in Paris, thanks mainly to Zborowski’s tireless promotion. Throughout the last years of the artist’s life, the dealer proved many times to be Modigliani’s greatest champion and financial guardian, often giving the artist cash advances and paying off his debts. But despite his generosity and effusive encouragement, there was a profit motive behind Zborowski’s actions, and his support for the artist was laced with a genuine concern for selling his paintings. Like Modigliani, Zborowski was often heavily in arrears, and his career was marred by financial mismanagement that eventually resulted in bankruptcy by the time of his death in 1932. Zborowski’s dependence on the profitability of his artists was well noted by his contemporaries, who were sometimes surprised by the inappropriateness of his callous behaviour. Kenneth Wayne provides an account of an exhibition of Modigliani’s work in 1919: “During the exhibition, Modigliani suffered a serious relapse in health, and it looked as if he were going to die. As Osbert [a collaborator on the exhibition] described the situation: ‘…a telegram came for Zborowski from his Parisian colleagues to inform him (of Modigliani’s worsening health); the message ended with a suggestion that he should hold up all sales until the outcome of the painter’s illness was known. My brother, who was inexpressibly shocked at this example of businessmen’s callousness, showed me the cable, and Zborowski asked us personally to refuse to sell, if a possible purchaser was to appear.’ Zborowski was waiting to see if Modigliani died, in which case he would have immediately raised Modigliani’s prices” (Kenneth Wayne, Modigliani and The Artists of Montparnasse (exhibition catalogue), Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2002-03, p. 73).

Notwithstanding these accounts of his character, the dealer was deeply committed to selling Modigliani’s pictures, and readily expressed his fascination with the artist’s work. According to Modigliani’s contemporary, Francis Carco, there could be no mistaking Zborowski’s enthusiasm for these pictures: “When you went to see Zborowski, he would run out to buy a candle, pop it into the neck of a bottle, then lead you into a bare, narrow, desolate room, in one corner of which lay a huge pile of Modigliani’s works. By the light of the candle, he would show you absolute treasures, passionately caressing them with hand and eye, then, fascinated, he would begin talking, moving about the room, cursing the fate that weighed on Modigliani and spitting with disgust. The more he gestured, the more fluently words came to express his magnificent, surging enthusiam for these paintings: nudes, figures, and portraits, all painted without a thought for convention, in which Modigliani’s manner and art were dazzingly affirmed. ‘What poetry’ was his ecstatic cry” (Francis Carco, De Montmatre au Quartier Latin, Paris, 1927, pp. 171-73, reprinted in Modigliani, L’ange au visage grave (exhibition catalogue), Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, 2002-03, p. 275).

Comparables:

Fig. 1, Léopold Zborowski, photograph Klüver/Martin Archive

Fig. 2, The artist and Zborowski (two figures on the right) at Osterlind’s, Cagnes-sur-Mer, 1918. Photograph Archives Jean Bouret – Paul Guillaume.

Fig. 3, Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait de Léopold Zborowski, 1916, oil on canvas, Private Collection

Fig. 4, Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait de Léopold Zborowski, 1918, oil on canvas, Private Collection