Post-script: This piece was initially intended as a review of the exhibition ‘Takis’ at Tate Modern. Sadly, since the time of writing the artist has passed away, on the morning of the 9th of August. This piece has subsequently been revised as something of a tribute to a singular figure of contemporary art.

Takis was a versatile self-taught artist whose work never failed to engage the curious

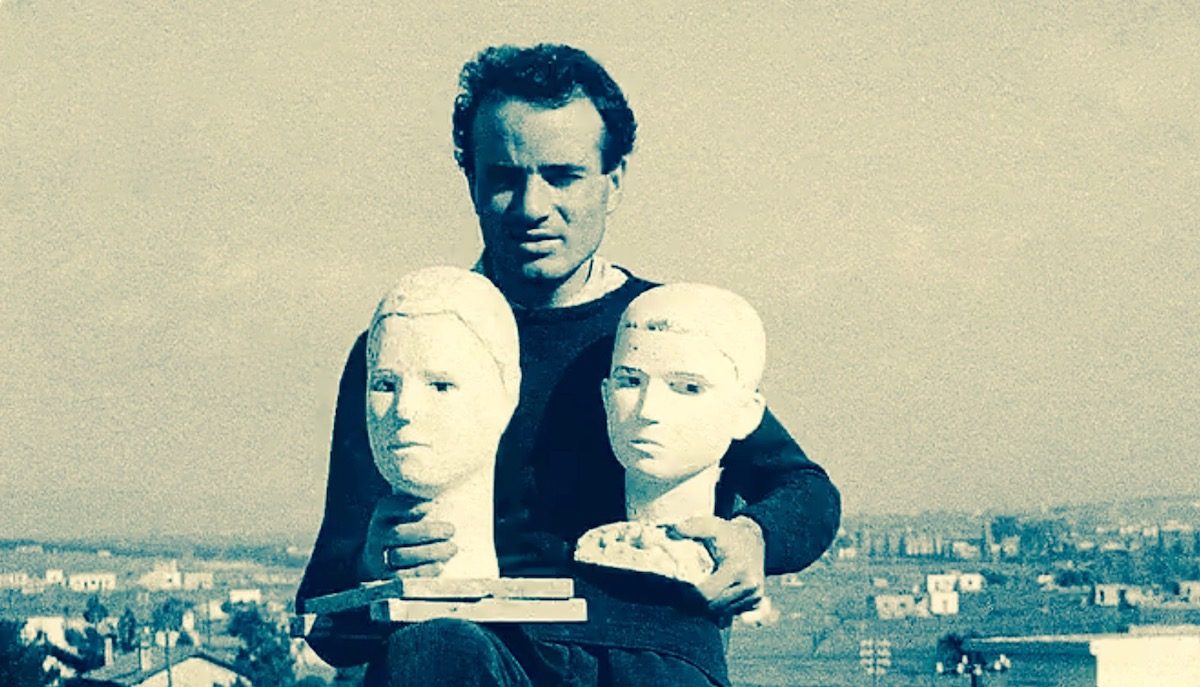

The late kinetic sculptor Takis (1925-2019) is currently being honoured with a large-scale exhibition at the Tate Modern, running through the 27th of October. Such a prestigious mark of recognition comes long overdue. When he passed away on the 9th of August, just a matter of weeks into the duration of his retrospective at the Tate, he was already ninety-three years old, so it comes as something of a relief that this critical corrective reassessment should have been formulated just in the nick of time.

Though outwardly lugubrious towards the machinations of the art world, I am convinced that this celebration of his seven-decade long career could not have failed to touch even him, especially given the importance that London and the British avant-garde of the 1960s held in Takis’s early development as an artist.

Takis cultivated a rich body of work over a lifetime that saw him zip around Athens, Paris, London and New York like some countercultural Zelig, rubbing shoulders with some of the leading figureheads of the post-war cultural milieu. However, while many of his (now mostly deceased) contemporaries from the creative circles in which he mixed have gone on to gain international renown, Takis’s work has of late remained generally neglected within the wider critical sphere.

This may perhaps be simply as a by-product of the artist’s longevity and gradual fade into relative obscurity as he relocated back to his native Greece in his later career. His work was admired and remarked upon by Marcel Duchamp, who with a characteristic pun described him a ‘gay labourer of magnetic fields’ (Takis returned the favour by dedicating an energy-harnessing floating contraption to the artist, topped with a rotating bicycle wheel, while a research fellow at MIT).

While he is something of a cult hero in France and his homeland, most anglophone audiences remain better acquainted with his contemporaries, such as Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely. Takis’s work stands apart from that of other kinetic sculptors due to his innovative introduction of magnetism into art, utilising unseen forces and energies to revitalise sculpture by suspending physical forms in space.

His large-scale outdoor totemic sculptures (not on view at the Tate show), large metallic columns topped with spherical components that catch the wind as they slowly rotate, encapsulate the artist’s preoccupation with unseen forces, as they turn, they create a bewitching sound that puts one in mind of the aeolian harp of antiquity. Takis continued to be fascinated by the culture and technology of ancient civilisations and often referred back to figures from Greek mythology even as he saw himself as a citizen of the world, untied to any one country. Like his musical contemporaries and collaborators John Cage and Nam Jun Paik, his work straddles Zen philosophy, Eastern mysticism and industrial technologies.

As much at home hanging out with the Beatles as Beat Poets and Parisian philosophers, Takis was a versatile, entirely self-taught artist whose work never fails to engage the curious viewer across multiple levels. His ‘Signals’, tall sculptures of metallic rods topped with blinking lights or repurposed scraps of metal, can be seen as icons of the Swinging Sixties’ obsession with futuristic technologies and positive utopian dreams. They could also alternately be read as remnants of a war-torn, post-human environment composed of decommissioned, defunct military hardware and abandoned machines blinking into oblivion.

Regardless, they work as beautiful objects in and of themselves, self-contained manifestations of otherwise unseen energies that sway like reeds in the wind, gently clanking together in unsynchronised harmonies of sound and movement. To initiated eyes, they become elemental totems from some bygone age or unknowable future.

Takis’s work is inherently sensual; it invites touch and participation, something that Tate’s heavily roped-off display otherwise prohibits (due, I am sure, to unavoidable loan and display conditions). Having had the chance to see much of it in person, there is something strangely bewitching about engaging with his work on a more intimate level. The tactile qualities of his sculpture and autonomy of the materials he employed are made much more evident through their gradual transformation over the course of time, something that is best observed from up close. Many of the works in the show date back fifty or sixty years and bear the marks of their journey across the decades.

His series of ‘Musicales’, for example, sound-based pieces consisting of a suspended needle that clangs against a taut piano wire at various intervals as it is attracted by the pull exerted by an electromagnet, create a cacophonous symphony that the artist links to the sounds of the cosmos. These works are just as exciting to me in their physical imperfections, in the aged cracking panels and the dark marks where needles have struck against wood over years of vibrations. Takis, who saw himself as an intuitive scientist as much as an artist, has little time for the sort of polished sheen that makes many of his peers now seem somewhat precious by comparison. He strips material forms down to their bare essentials to better convey the unseen forces of our universe in the most direct way possible. This might make his work seems relatively simple in construction, but such an approach belies a great complexity of thought and a deep well of references that the artist returns to with an obsessive vigour.

It is a pity that some aspects of the artist’s varied output are not represented within this current exhibition. Perhaps the curators of the show aimed to streamline his career down to its most vital components or were simply limited in terms of space and loans, unlike the definitive retrospective that the Palais de Tokyo held in 2015, a true mark of the breadth and variety of Takis’s vision. This means that, while the current show represents a selection of the artist’s best-known series, many of his experimental forays are missing, including his bizarre ‘Erotiques’, magnetic sculptures that incorporate fragmented human forms taken from life casts, usually focusing on sexual components. In some of these sculptures, such as his brazen ‘Sebastian’ (a full-length male nude with pronounced erection), small metallic elements are suspended in mid-air by concealed magnets and act like arrows, drawing lines towards the body to emphasise erotic attraction and connecting it to other invisible forces at play around us. It is a decidedly Epicurean view on the interconnectedness of all things and the vitality of pure sensual pleasure, albeit one that threads a fine line between the arcane and the absurd.

These are certainly artworks that represent a particular cultural moment, and probably represent the most outdated aspect of Takis’s otherwise timeless oeuvre. They do, however, serve to provide an interesting link between the violent corporeal compulsions latent within Surrealism, the art movement à la mode at the time of the artist’s birth, to his later technological impulses. As a Kafkaesque amalgamation of body and the machine, these sculptures shine a different light upon the kind of kinetic synthesis between form and movement that Takis pioneered. In this censorious time, one hopes that the more prudish fractions within the critical community won’t overlook this series in future studies on the artist’s wider practice.

The artist’s extensive studies into the effects of magnetism upon the regulation of the body, through the form of magnetic bracelets and headbands, solar yoga (utilising solar energies to revitalise mind and body), many industrial patents and deep-rooted interest in the technologies of Ancient Egypt and lost civilisations such as Atlantis also remain generally unremarked upon. Empty woo-woo talk, I hear you say? Perhaps. But these more eccentric forays represent an intrinsic component of the artist’s more extensive practice, feeding and informing his creative practice. Denying such aspects of Takis’s practice seems to imply a form of curatorial whitewashing based on the current shift away from the artist-as-shaman towards a much more sober, socially engaged view of art as an expanded field of interconnected activities. Where this trend will leave idiosyncratic outliers such as Takis in future surveys of twentieth-century art remains to be seen.

In fact, Takis himself readily identified himself as a scientist (of an intuitive kind) much more readily than he did an artist, and always sought to eradicate the distinctions between the arts, sciences and all other aspects of life. The serendipitously timed Olafur Eliasson exhibition also on show at the Tate Modern only goes to show how prescient his work now feels in light of a new generation of artists utilising (admittedly, mostly digital) technologies in their work. There is something special, however, about Takis’s outdated machine constructions, which at the time of their making already seemed like a paean to rapidly disappearing technologies. The tactile quality of the machine is being lost and with it our personal connection to the invisible forces that help coordinate our lives.

In breaking down the barriers around the creation and display of art, Takis came to represent a powerful figurehead for artists’ rights when he forcefully removed his sculpture from the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1969 as he didn’t agree with the way in which it was being used to fulfil a particular curatorial remit agree, kickstarting the influential Art Workers Coalition Movement (AWC).

One particular image that stands put from this time is a poster, using a photograph taken during Takis’s sit-in at the MoMA, with a slogan reading ‘Art-Workers Won’t Kiss Ass’. Takis, who as a young man spent six months in prison for his part in the resistance against the Metaxas dictatorship, has made a life’s work of not kissing ass, be it to the whims of the art market, societal niceties and changing tastes.

The artist’s memory will remain through all those who have been moved by the indelible attraction of his work and his creative legacy will live on through the work of the foundation that bears his name, situated in the hilly outskirts of Athens on a particular site referred to locally as Gerovouno (Holy Mountain). This was the place that Takis first started to build what would become his home, studio, museum and final resting place over fifty years ago, chosen, of course, because of its particular magnetic qualities.

Words/Photos: George Micallef Eynaud Top Photo Courtesy Tate Via Twitter Words © Artlyst 2019