Before surrealism had a name, Giorgio de Chirico was painting its blueprint. Born in 1888 in Volos, Greece, to Italian parents, his childhood was steeped in the contradictions that would define his work—classical mythology clashing with industrial modernity, the familiar made strange.

In Munich’s reading rooms, Nietzsche’s fractured aphorisms and Schopenhauer’s icy fatalism entered his bloodstream like slow-acting reagents. Here were not philosophies to be studied but corrosive agents – time’s unreliable viscosity, memory’s deliberate betrayals, the way solid objects dissolved upon prolonged inspection – that would permanently alter his way of seeing. The paintings that followed didn’t illustrate these ideas; they became the chemical reactions themselves.

“To become truly immortal, a work of art must escape all human limits. But once these barriers are broken, they will enter the realms of childhood visions and dreams.” – GDC

By 1910, de Chirico was in Florence, producing the first of his Piazze d’Italia—those unnerving city squares where shadows stretch too long and perspective warps under some unseen pressure. These aren’t landscapes but psychological diagrams. The arcades echo with absence; statues cast living shadows; trains puff smoke in the distance, eternally arriving, never arriving. He called this phase Pittura Metafisica (Metaphysical Painting), though it was less a movement than a private reckoning with the ghosts humming beneath ordinary things.

De Chirico in 1970, photographed by Paolo Monti. Fondo Paolo Monti

What separates de Chirico from the surrealists who later claimed him is his restraint. Where Dalí liquefied clocks, de Chirico placed them next to a rubber glove and let the unease build on its own. His still lifes—mannequins, biscuits, dismembered drafting tools—aren’t grotesque, but their arrangements suggest a logic just beyond comprehension. The effect is less a nightmare than the moment upon waking when the dream’s meaning slips away.

The 1920s saw him abruptly abandon his metaphysical style, turning instead to brittle neoclassicism. Critics accused him of retreating into pastiche, but the later work—knights in fog, gladiators with faceless helmets—retains his old obsessions: antiquity as a haunted house, history as something that doesn’t end but accumulates in layers. Even his worst detractors couldn’t deny his influence. Everyone from Magritte to Hopper stole from him, though few understood that his actual subject wasn’t objects themselves but the silence between them.

De Chirico’s final decades were spent in Rome, painting variations of his early masterpieces while publicly dismissing modern art as “the cult of the ugly.” It was a performance, of course—the same sly provocation that had always animated his work. When he died in 1978, he left behind a paradox: an artist who invented a visual language for the unconscious, then spent a lifetime pretending it was just good draftsmanship.

His legacy lingers in places where reality buckles—in films where empty streets hum with menace, in fashion shoots that turn mannequins into lovers, and even in video games where architecture bends to suggest a puzzle with no solution. De Chirico didn’t paint dreams. He painted the moment before the dreamer realised they were asleep.

Key Works:

- The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon (1910) – The first metaphysical landscape, born from a migraine hallucination in Florence’s Piazza Santa Croce.

- The Song of Love (1914) – A rubber glove, a classical head, and a green ball collide on a wall. Breton called it “the first surrealist painting,” though de Chirico scoffed.

- Hector and Andromache (1917) – Mannequins embrace in a square, their features sanded away. Grief made architectural.

Top 10 Highest Auction Prices for Giorgio de Chirico

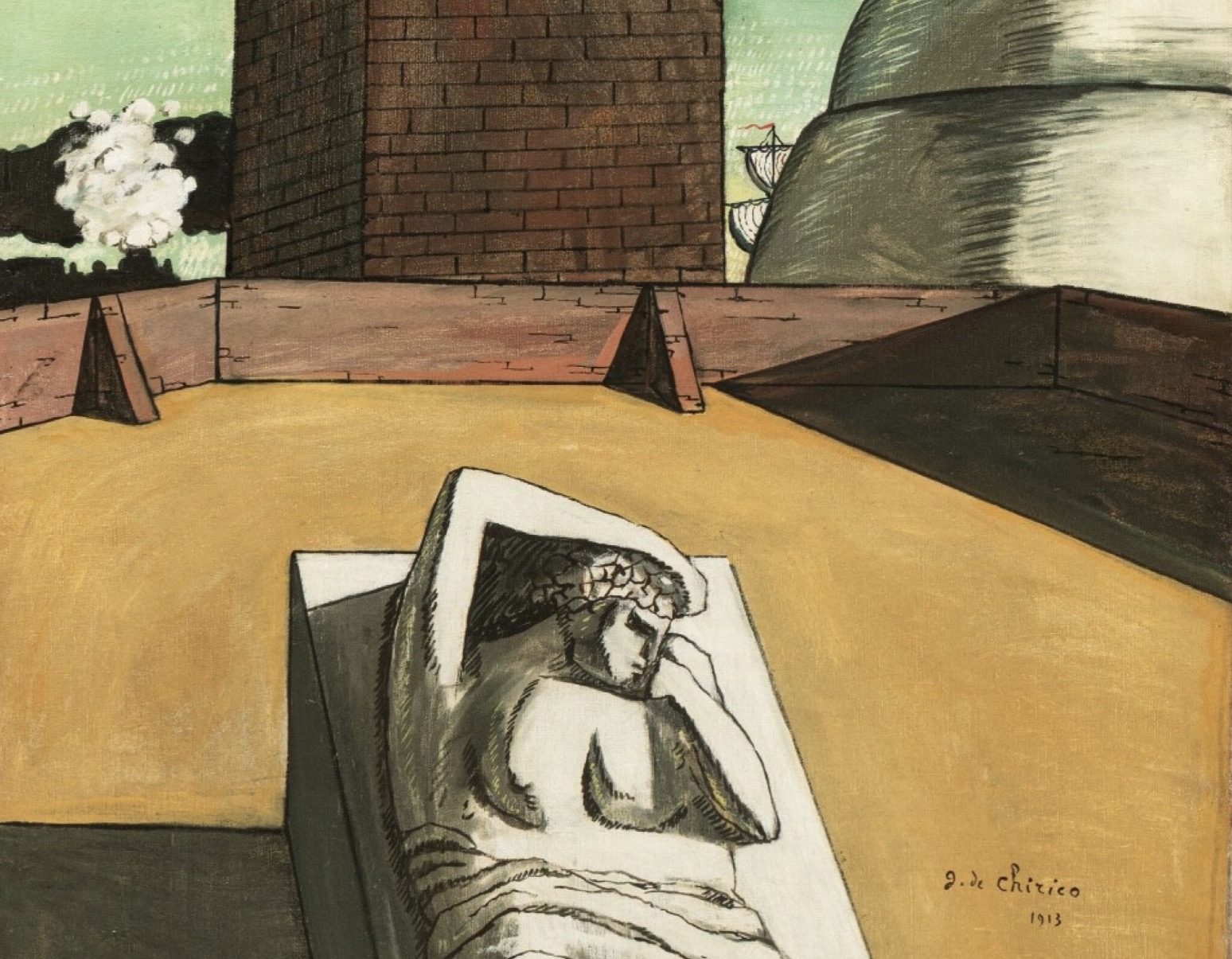

- “Il pomeriggio di Arianna (Arianna’s Afternoon)” (1913) Top Photo Detail

- Price: $15.9 million (Christie’s New York, 2019)

- A key metaphysical work depicting a classical statue in a deserted plaza, emblematic of de Chirico’s haunting early style.

- “Ettore e Andromaca (Hector and Andromache)” (1924)

- Price: $12.1 million (Sotheby’s London, 2010)

- One of his iconic mannequin-figure paintings, blending myth and modernity.

- “Il grande metafisico (The Great Metaphysician)” (1917)

- Price: $10.8 million (Christie’s New York, 2014)

- A towering, fragmented mannequin against an architectural backdrop—pure metaphysical enigma.

- “Piazza d’Italia (Italian Square)” (1955, later version of a 1913 composition)

- Price: $9.1 million (Sotheby’s London, 2015)

- A reworking of his famed deserted squares, showing his late-career return to early themes.

- “Le Muse inquietanti (The Disquieting Muses)” (1947, later version)

- Price: $7.6 million (Christie’s London, 2018)

- A haunting reinterpretation of his 1918 masterpiece, featuring mannequin-like figures in a surreal landscape.

- “Interno metafisico con biscotti (Metaphysical Interior with Biscuits)” (1916)

- Price: $6.9 million (Phillips New York, 2019)

- A still life of geometric objects and biscuits exemplifies his eerie domestic scenes.

- “La torre rossa (The Red Tower)” (1913, later version)

- Price: $6.3 million (Sotheby’s London, 2017)

- A dreamlike Italian piazza dominated by a looming red tower.

- “Il trovatore (The Troubadour)” (1922)

- Price: $5.8 million (Christie’s London, 2011)

- A neoclassical-inspired figure with an ambiguous, theatrical presence.

- “Natura morta metafisica (Metaphysical Still Life)” (1916)

- Price: $5.4 million (Sotheby’s New York, 2014)

- Architectural elements and disjointed objects in a silent, enigmatic composition.

- “Ville romane (Roman Villas)” (1924)

- Price: $4.9 million (Christie’s Paris, 2017)

- A later work blending classical ruins with his trademark unreal light.

Market Insights

- Early metaphysical works (1910s–1920s) dominate his top prices, prized for their pioneering surrealist tension.

- Later reworkings of his own compositions (1940s–50s) still fetch high sums, though critics debate their merit.

- Mannequin & piazza themes are his most sought-after, influencing everyone from Magritte to Hopper.

- “Il pomeriggio di Arianna (Arianna’s Afternoon)” (1913) Top Photo Detail

De Chirico’s genius lay in making the world feel unfinished—a stage waiting for actors who never come. Walk through any city at dusk when the light turns liquid, and you’ll see what he meant.

Top Photo: De Chirico Il pomeriggio di Arianna (Arianna’s Afternoon) 1913