The highly anticipated first UK exhibition of Keith Haring’s work has opened at Tate Liverpool. It is vast, covering most aspects of his work and career. This was my first experience seeing so many pieces by this seminal figure from the 1980s, in the flesh, so I was curious to learn more about the man.

Haring’s activism is strong in his art, in many ways, it is his art – AL

Haring worked in many mediums with a wide breadth of communication. He seems to have used all avenues to explore his art and to engage with the people and culture around him.

Brought up in Pennsylvania and taught to draw cartoons by his father, Haring enrolled at The School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. He found himself unsuited to the conventional route of art training and wanted to explore his work on a broader level, with a more profound meaning, and this he certainly did in his short lifetime.

My impression of the exhibition was that of an edgy urban feel, bold drawings, cartoons, textiles, something quite tribal. There is a lot of black and white and vibrant colour happening in Haring’s work. In ‘Untitled, 1982, Acrylic paint on wood’ we see Disney characters painted on rough wood, the beginning of his art connecting to a media-dominated society. There is also a DIY feel to his work with things having been made out of products such as grommets, vinyl and acrylic paint on tarpaulin. This rough and ready surface was one of his favourite materials for painting.

On entering the show, there was vibrant energy within the space. Conversations about the early eighties echoed around the galleries and it was apparent that many people shared a similar experience of thoughts and ideas. Growing up during this time period, music, politics, and culture flourished. This was interesting to observe through the eyes of others at the exhibition.

As you walked on, the paintings become bolder and more abstract, there was a strong feeling of movement and design, poster meets graffiti art, cartoon, drawing and activism all combined. Haring used symbols in his art, barking dogs, symbolising a call for attention and outbursts of anger and crucifixes occur frequently, apparently, the cross was a symbol of his criticism against organised religion which he felt condemned gay culture. Dollar signs also appear to represent his distaste of capitalism.

If you are lucky enough to see this exhibition, you can pick up a pamphlet which will direct you to the meanings of the symbols in Haring’s art. This is useful, mainly as his work is quite semiotic and linguistic-based. There are films and a night club feel in parts of the gallery. You start to see the magnitude of work that Haring carried out.

Haring’s activism is strong in his art, and in many ways, it is his art, but his love of drawing conveys his enjoyment and how he flows with this attitude without hesitation, his works also bridge the gap between high art and popular culture, in other words, Street-art and Gallery art.

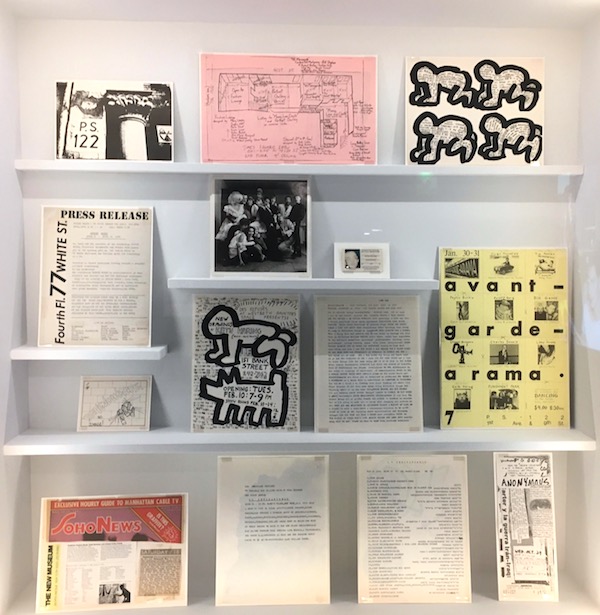

Haring used alternative spaces to display his art. There were few opportunities in the 1980s for young artists to exhibit in Manhattan due to the economic downturn. As a result artist, poets and activists joined up to create art and voice their thoughts on important issues such as Apartheid, AIDS and Nuclear Disarmament; through a vibrant art and party culture which emerged building on the DIY attitude of the punk pioneers. During this time, Haring organised an exhibition at Club 57. He would exhibit his own drawings and video works as well as curating shows featuring his friends and peers. Located in the basement of a Polish Church on St Marks Place, it became an artist hangout and a venue for performance, poetry, music, film screenings and art. It’s atmosphere leaned towards stylistic anarchy improvisation and hedonism.

It was in 1980 that Haring exhibited with Basquiat, Jenny Holzer, Lee Quinones, the most influential American artists to emerge from the New York City subway graffiti movement. Graffiti, Rap and Street Art all came together which led to an exhibition at Mudd Club entitled Beyond Words. The exhibition was relevant to the politics and events of the time. Haring went on to exhibit in The Times Square Show. ”The Times Square Show is often referenced as a groundbreaking exhibition that inaugurated new trends in contemporary art. In this unstable environment, young artists formed a community in which possibilities abounded. The idea that there was nothing at stake—and thus nothing to lose—opened up the culture to a frenetic social exchange where music, art, film, and fashion took on their own identities apart from trends dictated by industry standards. The ability to take risks broke down boundaries and encouraged collaborations among artists who experimented by combining traditional mediums with new media, forming collectives and challenging the accepted modes of making and showing their art. In this context, the TSS can be understood as an exhibition that introduced powerful forces in contemporary art that, decades after, continue to permeate and influence trends and practices in making art.”

There is a youth-culture angle to Haring’s work. Responding to music and politics, his work emanates the time, particularly that of politics but also the night club scene. I found it very interesting how he used night clubs as his canvas to show his own work and that of fellow artists. He would use the basements and the music from the clubs would become part of his art, the urban city culture influencing his work visually, emotionally and environmentally.

In 1982- 1984, Haring created The Blacklight Room in a basement gallery. The Black lightroom was a space Haring had set up within an art gallery to replicate a nightclub to exhibit his art. Club music of the time plays in this room at Tate Liverpool and is representative of Haring’s wish for his art to remain accessible to a wide audience. Haring took a different approach at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery to break down social boundaries. Haring presented his fluorescent DayGlo paintings and objects under UV light, the experience was heightened with hip hop music played by Juan Dubose, Haring’s partner, who acted as DJ in the gallery.

This combination of music with his art was something Haring celebrated, and both genres came together in his work, creating a multi-sensory experience. I really enjoyed this. It echoed the culture of the time, that of his friends, the literary graffiti artist Basquiat and other artists who were immersed in graffiti art of the time.

As he became famous, Haring worked hard at keeping his art engaged with the street.

He didn’t want to become divorced from the roots of his work, that of the urban landscape and the masses, especially as he hated the elitism of the New York art establishment.

There is a Banksy ethic to his work. I see similarities in drawing attention to politics and media, but Haring also had a willingness to sell off his art at low prices in order to help young collectors and fans acquire his work. Haring wanted to remain with the people and not jump over to the other side of the capitalistic gallery establishment. However, the question of how artists maintain their integrity supporting a left-wing ethos versus their eventual fame, which results in making vast amounts of money is a conundrum. This often came up, and it was mentioned, and there were conflicts of wanting to be part of the bigger picture in the art world, but also wanting to hold on to his identity.

Haring found ways of using his money, recycling it, putting it towards charity, campaigning to raise awareness of AIDS and using it for positive causes. This provided a concrete outlet for the rewards of his works.

Haring became a popular and recognised icon of the times, his artwork was printed on merchandise and he was also on television and his work was celebrated in his lifetime. It was at this point he had to tread carefully so to avoid becoming too absorbed in the media he was criticising.

Andy Warhol became a significant mentor for Haring. There were some similarities to their approach in making art. Both used the media and popular culture, film and performance in their work. The main difference was that Haring’s work was more social conscience and engaged, whereas Warhol was into the aesthetics of personality, debunking mass produced items by making them into high art forms, rather than stating political thoughts through activism. It must have been an interesting conversation between them.

The eighties were a time of political upheaval, apartheid, nuclear protest and the outbreak of the AIDS virus. Haring was an early communicator of AIDS awareness. In a time when HIV was linked to the gay scene, he helped get the message across and instead of telling people not to have sex, he created posters and flyers highlighting safe sex.

It is depressing to note that President Reagan didn’t acknowledge AIDS or make it a policy issue. For many years after it had become an epidemic and with so many people dying of the disease, little was done about this public health crisis. Many of Haring’s friends died of AIDS, and he also succumbed to AIDS in 1990. Prior to this, in 1988, he had set up the Keith Haring AIDS Foundation to raise awareness.

Overall the exhibition is reminiscent of the culture in America during the early and mid-eighties. Haring’s street art and activist art is very much a response to the times. The economic difficulties, the drug culture, the AIDS epidemic but also, his own artworks explore the flow of free drawing, taking it off the paper and onto a variety of surfaces that reflecting the material of popular culture.

The more you look into Haring’s work, the more intriguing it becomes. Many of the themes are sexuality charged with safe sex a priority, but also other political messages manifest. In the Tate exhibition, information Labels are exhibited on the floor, not next to the works as not to distract.

Haring embraced the streets of New York, using these spaces for showing art

Haring likened graffiti art to Chinese calligraphy. There is a feeling of calligraphy in his work with the letter-forms and symbolic designs. He admired the “literary graffiti” of Jean -Michel, who he befriended. Haring’s use of public space is broad and inspiring, the use of subways, walls, nightclubs, and the reinventing of art gallery spaces.

Haring had incredible foresight and was already predicting how technology would influence and change society for the worse. In his work, ‘Untitled’ 1983, he depicts with vinyl paint on tarpaulin a surrealist graffiti painting of a computer as some kind of alien centipede. The image on the computer within the painting is quite strange and shows a person with a tail being yanked. It seems Haring is mocking the new culture of technology.

On the same theme of technology, the exhibition displays a massive 30-foot long mural titled ‘Matrix’, 1983, ink on paper. It is an incredible piece of art that yet again draws attention to the negative aspects of computer society.

If you saw Tate Liverpool’s previous exhibition, Fernand Leger, you would be aware of how he viewed the machine, dominating society. Leger was expressing his views of the machine-age 60 years before Haring. He joined the communist party and describing the machine’s negative effect on society through his ‘mechanical forms. In Haring’s work, it is obvious he despised the computer and saw it as a threat, something that was turning people into passive consumers. It is intriguing when you start comparing artists and seeing how society and the machine affect each other in different ways through time and through their art.

Keith Haring is one of the most socially engaged artist/activists of the last forty years. Don’t miss this powerful exhibition!

Words/Photos Alice Lenkiewicz © Artlyst 2019

Keith Haring 14th June – 10 November 2019 Tate Liverpool