Osborne’s project began, like many honest ones do, from necessity. Confronted by her own experience of menopause, she realised how little there was in the public realm that reflected it truthfully. There was information, yes—clinical, biological, packaged—but no imagery, no real language for what it feels like. So she did what artists often do when faced with absence: she filled it.

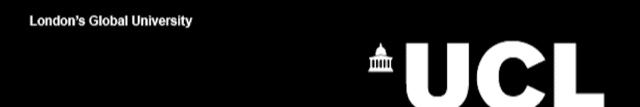

The result is a collection of 80 portraits of women who are either living through or have emerged from the menopause, each photographed in her “happy place.” These are not studio shots designed to flatter. They are lived-in, luminous, and quietly confrontational. Each sitter occupies her own world—a garden, a kitchen, a shoreline—and each space tells you as much as her expression.

“What does the menopause look like?” Osborne asks. Her answer: not one thing. It appears to be a mix of strength, exhaustion, humour, and relief. It seems that women are reclaiming a narrative that was never intended to serve them.

The accompanying interviews are as unfiltered as the photographs. The women speak with candour about rage, grief, and liberation. Some describe the body’s betrayal; others describe a profound homecoming to the self. Osborne’s editorial hand is light—she listens more than she leads—and that trust gives the book its strength.

There’s no gloss or fake empowerment here. What emerges is texture: the messy, conflicting realities of a transition that resists simplification. The work feels grounded in conversation.

What distinguishes A Portrait of the Menopause from other similar projects is its tone. It’s not an attempt politicise; it’s an act of documentation. Osborne approaches her subjects with respect rather than reverence, and the result feels communal rather than performative.

The book is a patchwork of small revelations. There’s something deliberate in its everyday defiance of showing women as they are, in places where they feel most themselves. In that way, it does something rare: it is portraiture without spectacle.

A Portrait of the Menopause feels like an act of reclamation. Osborne’s images invite empathy. They portray an honesty, humour, and the kind of beauty that comes with endurance.

It’s a book that answers a question we should have stopped asking decades ago—not what’s wrong with menopause, but why have we been so afraid to look at it?