After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art explores the period in modern art from the last Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1886 to the eve of the First World War in 1914. In the words of co-curator MaryAnne Stevens, it’s a period that can “claim to have broken links with tradition and laid the foundations for the art of the 20th and 21st centuries.” The exhibition seeks to explore the complexities of this period and its wider cultural manifestations.

….the influence of religion and spirituality, without which the story of modern art cannot be fully understood.

Beginning with Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin and ending with Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondriaan, the exhibition shows us a whole host of artists who, as Dr Gabriele Finaldi, Director of the National Gallery, notes “reshaped the aesthetic landscape in Europe around 1900” through their radical outlook.

A key work in this regard is Maurice Denis’ ‘Homage to Cezanne’ (1900), which shows a group of artists, notably the Nabis (Prophets), gathered in homage around one of Cézanne’s still lifes while meeting in art dealer Ambroise Vollard’s Paris gallery. On the wall behind them hang paintings by Gauguin (who owned the Cézanne still life) and Auguste Renoir. The painting demonstrates the significance of Cézanne and Gauguin for artists, critics, family members and gallerists, including here: Odilon Redon, Edouard Vuillard, the critic André Mellerio, Vollard, Denis, Paul Sérusier, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, Pierre Bonnard and Marthe, Denis’s wife. The exhibition looks broadly at this and other remarkable generations through a focus on key centres of activity – Paris, Brussels, Barcelona, Berlin and Vienna – and movements – Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Expressionism, Fauvism and Cubism – that move inexorably in the direction of abstraction.

The paintings and sculptures included illustrate the main themes in the development of the visual arts in Europe in this time period: the break with conventional representation of the external world and the forging of non-naturalist visual languages with an emphasis on the materiality of the art object expressed through line, colour, surface, texture and pattern. The move was principally towards simplification of form, patterned surfaces and an increasingly fractured, mosaic-like application of colour, while non-naturalism also alerted the spectator to the new subject matter of art, ideas and emotions.

What is under-appreciated generally, as also within this exhibition, is the extent to which the spirituality of the artists involved played a significant role in bringing about these developments. On the surface, these movements seem to be primarily about the materiality of the art objects themselves, but often below the surface of these developments are a complex of spiritual motivations and understandings.

Cézanne wrote that he had “worked for years trying to… reconstitute the petites sensations” that he got from nature. As Paul Portugés has demonstrated, Cézanne “vowed to dedicate his art to a recreation of truth and a celebration of nature and the Eternal by allowing his emotions to be included in his portrayal of reality.” For him, as he explained in letters to his friend Émile Bernard, this was “a means of getting close to the eternal in the every day, the sensation of the Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus.” He used proper perspective with the pictorial language of squares, cubes, and triangles “to reconstitute the impression of solidity” that he thought he could “think-feel-see” when looking at a motif like Victoire (e.g., ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire’, 1902–6), a spectacle “that the Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus” had spread out before our, and his, eyes.

Van Gogh wrote that he wanted “to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolise, and which we seek to convey by the actual radiance and vibration of our colouring.” Every element of Van Gogh’s work is infused with the energy of colour, light and movement, which ultimately derives, for him, from the sun as a sacred source animating nature. Robert Rosenblum notes that, for Van Gogh, the sun “has an almost supernatural power”. Its location, in paintings such as ‘Landscape with Ploughman’ 1889, “is that which, in earlier art, one might have associated with a symbolic representation of an omnipotent deity”, and its form and colour “suggest that this is, in effect, the pantheist’s equivalent of a golden halo.”

In one of his many letters, Van Gogh wrote that Bernard would have been better advised “simply to paint real olive trees” rather than ‘Christ in the Garden of Olives’ 1889. As a result, Rosenblum suggests Van Gogh was one of many artists “who tried to create, consciously or unconsciously, a religious sentiment in things observed that would be far more truthful to their personal experience of the supernatural than the perpetuation of traditional Christian iconography.”

Gauguin visited Brittany seeking “wildness and primitiveness”, a search that was pervasive in this period and which eventually led Gauguin to Tahiti. That search, although often patronising – Kandinsky, for example, wrote of “savages” and “civilisation” – was also acknowledged to be religious, as with Guillaume Apollinaire’s writing of the “the sublime beauty” of religious works of art “executed by anonymous African artists”. It was religion that Gauguin encountered in Brittany – the sincerity and purity of the Breton people and their Catholic faith – a faith that had already made again a Catholic of Bernard, who, by sharing with Gauguin the cloissonist techniques he had developed with Louis Anquetin enabled Gauguin to begin painting pictures, including ‘Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel)’ 1888, that are positive observations of faith of others.

Gauguin’s “catalytic encounter” with the fervent Catholic Bernard in Pont-Aven during the summer of 1888 led to the recruiting of Sérusier in the autumn and then, through ‘The Talisman, Landscape in the Bois d’Amour’ 1888, the conversion of the Nabis group in Paris to synthetism. Interestingly, Gauguin’s works with a Catholic influence were painted in the same period that James Ensor in Brussels was also eliding his story with Christ in a similar way to that of Gauguin.

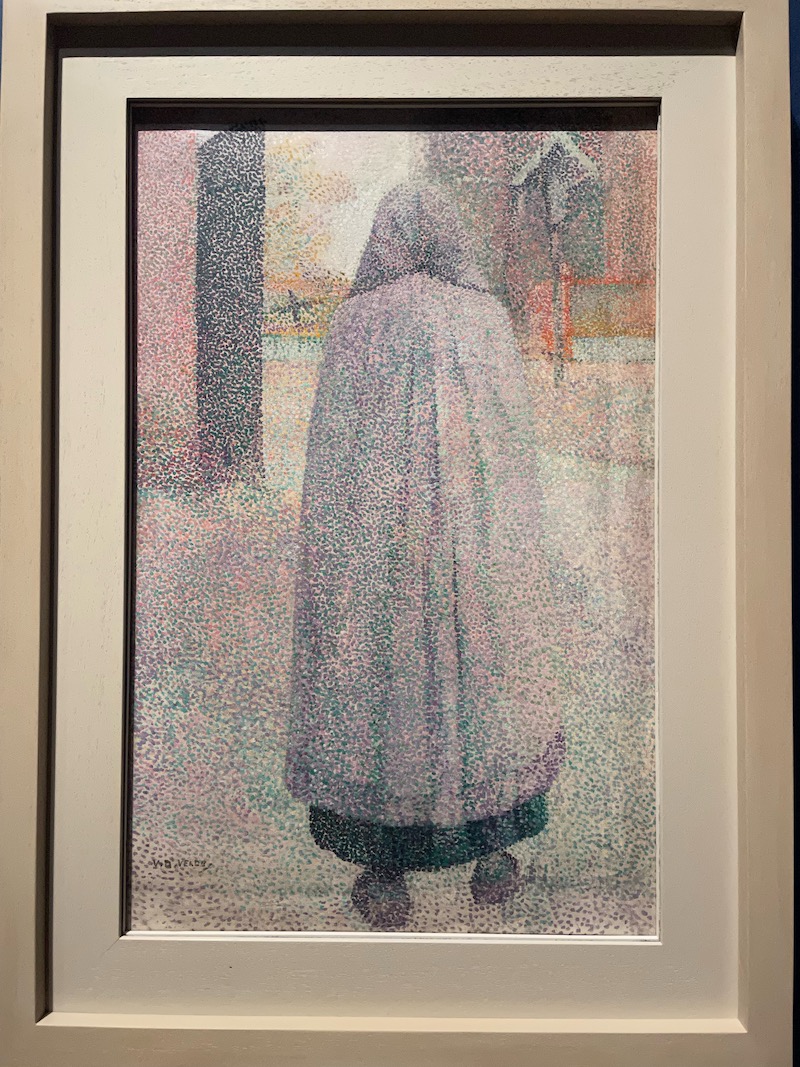

The Nabis, too, were primarily committed Catholics, with Jan Verkade entering religious orders at the Beuron Monastery, where Fr Desiderius Lenz, Sérusier led its art school, after visiting Beuron, permeating his work with religious symbolism including exploration of the Golden Mean, while Denis, who was exceptionally influential as an artist and theorist, set up the Studios of Sacred Art with George Desvallières. Through their influence, Gauguin became “an important precursor of the revival of sacred art.” Bernard’s ‘The Pardon, Breton Women in a Meadow’ 1888, Denis’ ‘The Evening Wash, by Lamplight, or Motherhood at Le Pouldu, Evening Effect (version 1)’ 1899, George Minne’s ‘Kneeling Youth of the Fountain’ 1898, and Henry van der Velde’s ‘Going to Church’ about 1892 all show us the widespread influence of Catholicism on the art of this period, as does the career of Jan Toorop whose prints of saints made him one of the most reproduced artists of his time.

If we then skip to the end of the period documented by this exhibition, we find there a different kind of religious influence holding sway. Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondriaan, on their separate journeys to abstraction, were both deeply impacted by Theosophy, the religion principally established in the United States during the late 19th century by Helena Blavatsky.

Many of Kandinsky’s observations in Concerning the Spiritual in Art about form, colour and spatial relationships, which appear to be purely aesthetic, actually derive from Thought-Forms, the theosophical classic by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater that was translated into German in 1908. Mondriaan’s neoplasticism was directly influenced by M. H. J. Schoenmaekers, a Theosophist and mathematician, who wrote in a 1915 essay of “the line of the horizontal force”, the “vertical and essentially spatial movement of the rays” and “the three essential colours” of yellow, blue, and red. Roger Lipsey states that: “The impact of Theosophy on art was selective but enduring. Its multilevel universe, its promise that human consciousness can evolve, its assurance that human beings belong to an unseen world of grace and power no less than to the daily grind, its rudimentary abstract imagery and colour symbolism – all of these would enter into the work of a handful of pioneering modern artists in forms now familiar to many of us.”

Massimo Introvigne has set out how Sixten Ringbom, who first identified the influence of Theosophy on Kandinsky, experienced considerable ostracism from those who did not want modern art to be associated with irrationalist and disreputable “cults”. A similar downplaying for similar reasons has featured in critical assessment of the influence of artists such as Bernard and Denis. After Impressionism, acknowledges the significance of Denis in his time but speaks of his evoking of

Christian iconography as if it were an isolated obsession, rather than recognising the widely held engagement of many artists with religion in this period and the influence that that engagement actually exerted on Post-Impressionism and Symbolism.

After Impressionism includes many of the most influential artworks and artists from this period; as such, it is a must-see blockbuster exhibition which, while highlighting many of the key strands in the story of how modern art was invented, nevertheless continues the critical downplaying of other strands, particularly the influence of religion and spirituality, without which the story of modern art cannot be fully understood. After Impressionism is not to be missed, but, as you visit, be sure to fill in the gaps in the story as told.

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, 25 March – 13 August 2023, National Gallery

Words by Revd Jonathan Evens, Photos by Sara Faith ©Artlyst 2023